Real Reasons These Video Game Characters Were Killed Off

Death is an understandable part of video game stories. However, some deaths leave the reader downright baffled, wondering why their favorite character had to make an untimely exit. Fortunately for those seeking understanding, everything happens for a reason, and sometimes all it takes is a deeper dive into the storylines to figure out what those reasons are. With that in mind, here are the real reasons some great video game characters were killed off. Reader, beware, as here there be spoilers galore!

Aeris

One of the most famous video game deaths befell Aeris (or "Aerith" for the more hardcore players) in Final Fantasy VII. Her death became the inspiration for seemingly countless myths about ways to prevent it, ways to resurrect her character, and so on. The blunt truth is that Aeris stays quite dead, save for a weird vision Cloud has as part of the game's climax, but why did she die in the first place?

The most basic answer is that Aeris was "fridged." For those not in the know, "fridging" is shorthand for "women in refrigerators." If that sounds incredibly specific, that's because it is: the term came about after a 1994 Green Lantern comic in which the hero's girlfriend has been murdered and stuffed into his refrigerator. Comics legend Gail Simone noticed that this incident was merely the latest in a long line of comic book women who die to motivate a male protagonist.

That's ultimately why Aeris dies. Don't believe it? The truth lies in the fact that the narrative of the game would remain largely unchanged if the character had lived. There would still be a climactic fight with Sephiroth and the use of the "Holy" spell to save the world. The only reason that she dies is to give both Cloud and the player motivation to defeat Sephiroth. Aeris fans can only hope that the upcoming Final Fantasy VII remake does this great character more justice than the original.

Duncan

For players of Bioware's epic game Dragon Age, it's tough to not immediately like Duncan. He functions as the player's gruffer, tougher Obi-Wan Kenobi figure...a sort of father-figure and mentor as the player begins an adventure in a strange new world. He proves himself as a skilled diplomat and a powerful warrior, but this is not enough to save him from being killed in a dramatic battle (and not before he has single-handedly taken out a powerful ogre). Exactly why did this bearded badass have to die?

Call it the Ned Stark effect. Most of the time, beloved characters in TV shows and video games have a kind of perpetual plot armor, and viewers eventually grow accustomed to the idea that these characters can survive catastrophes that would kill a regular person. This breeds a kind of dramatic complacency, as it's tough to genuinely worry about the fate of characters if the viewer is reasonably sure they can never die. In his first book and its subsequent TV adaptation, George R.R. Martin changed the rules with Game of Thrones: he clearly set up Ned Stark as the typical fantasy protagonist, and then had his head chopped clean off. Martin did this for the same reason that the Dragon Age writers killed Duncan: it establishes that no one is truly safe in this universe. That sudden air of mortality hanging over all the characters in a player's party serves to invest them in the story like never before.

The Joker

The immensely successful Arkham games (Arkham Asylum, Arkham City, and Arkham Knight—oh, and their red-headed stepchild, Arkham Origins) faced a persistent dilemma of their own making. Part of what excited fans about these games in the first place was that the game makers were able to bring back some of the voice actors from the amazing Batman: The Animated Series, including Kevin Conroy as Batman and Mark Hamill as the Joker. This led many fans to conclude that this was meant to be in the same universe as the cartoon...an illusion that was shattered when the Joker definitively died at the end of Arkham City.

Of course, this is exactly why Joker had to die. The Batman cartoon was not in its own small bubble. Instead, it was connected to other animated shows such as Superman, Justice League, and the future-set Batman Beyond. If the games were in that universe, it would limit their stories, as fans of the cartoon already know the fates of characters such as Joker and Ra's al Ghul. Killing Joker definitively cuts that cord, freeing the team to do whatever they want with the characters while putting fans back in suspense, unsure of what will happen. This actually helps later games leverage that dramatic uncertainty by making fans wonder about characters that they might otherwise assume were cloaked in that aforementioned plot armor.

Booker DeWitt

Bioshock Infinite is a strange game. It's easy for first-time players to lose themselves in the gameplay itself, which serves as the ultimate in modern running, gunning, platforming fun. Those same players were likely caught by surprise by the mind-bending climax, in which players must willingly kill their protagonist, Booker DeWitt. The narrative reason he must die is that, due to some timey-wimey interdimensional shenanigans, his death prevents the rise of the big bad of the game (who is also Booker). The real reason he dies, though, is much more compelling.

His death is central to the player understanding the idea of the multiverse. The "infinite" in the title refers to infinite dimensions that are slightly different from what players are familiar with. The villain of the game, Zachary Comstock, is a version of Booker that found religion and became a murderous zealot. The man the players control through the game rejected religion and became a gambling, dissolute drunk. Another character, Elizabeth, convinces Booker to kill himself to break this cycle and save the future, but when players realize what this means, other aspects of the game suddenly make sense.

For instance, there are hints that Booker has tried and failed to do all of this before...that there have been over a hundred previous attempts to change the timeline. Instead of being the driving force in the narrative, players realize Booker is not just a cosmic speck, but one speck in a line of insignificant cogs in the universe. In this sense, they understand multiversal theory, questions of fate vs. agency, and the implications of religious thought influencing colonialism. Compared to the player, Booker had an easier time: all he had to do was die!

Noble Team

Halo: Reach stands among the greatest installments in the long-running series. For some players, it represented the zenith of Halo game design, marrying a fun and variegated multiplayer mode with a genuinely engaging campaign that served as a prequel to the main Halo series while still managing to surprise players as the game went on. Specifically, the squad of badass Spartan warriors that serve as our protagonists throughout the game start dying one by one, culminating in the death of the player's character at the end of the game. Why did these colorful characters have to bite the (space) dust?

It all comes down to dramatic irony. As everyone had to learn in high school, dramatic irony refers to what's created when the reader, player, or viewer knows something that the characters don't. A great example comes from Macbeth, in which viewers are aware of Macbeth's plans to kill the king when Duncan starts talking about how he absolutely and completely trusts Macbeth. This builds natural tension and suspense as viewers know what's going to happen without knowing exactly how or when.

The same thing occurs in Halo: Reach. Players shouldn't really be surprised to see characters die, because the beginning of the first Halo game has Master Chief and crew warping away from Reach, a planet that has been definitively lost to the evil alien Covenant. In fact, some of the advertising included the line "From the beginning, you know the end." Just as Shakespeare's audiences held their breath waiting for King Duncan to die, players went into each new level and cutscene waiting for their new favorite characters to be killed. This tension and suspense while awaiting tragedy may drive up blood pressure, but it's a hell of a storytelling technique.

The Colossi

Shadow of the Colossus remains one of the most haunting games that many players have ever experienced, even though it came out in North America way back in 2006. The initial premise of the game seems to be Video Games 101: the world is populated with strange and powerful monsters, and gamers have been conditioned since stomping their first Goomba to kill all monsters on sight. Players have also been conditioned to save the princess, and this game requires the character to kill these monsters to restore life to the lady the protagonist loves. As players kill these monsters one by one, however, they begin to realize how they've been misled by typical gaming conventions.

From a strict plot standpoint, it turns out to be a setup, and killing these monsters is actually making a bad guy strong and whole again. This revelation is tied to a greater emotional revelation, though. Specifically, the character is killing creatures who have done him no wrong in order to fulfill his own selfish wishes. He is very unambiguously the bad guy, as a strange invader killing gentle and mysterious creatures. The real reason they die is so that players can experience this emotional gut punch. It's basically the video game equivalent of the original I Am Legend novel, in which the human protagonist who has been killing and experimenting on zombie-like creatures finds out they are sentient beings with their own culture. To them, he is a legendary figure who kidnaps and murders them for reasons all his own, much like the player killing Colossi who have no idea why they are being murdered.

Lee Everett

It's thematically appropriate that Walking Dead fans can never really escape death. Of course, the functioning symbols of death are the numerous undead zombies littering the apocalyptic landscape of Georgia. The really scary part, though, is knowing that a favorite character can be randomly killed at any point. Eventually, the show's cruel creators leveraged that into the ham-handed finale of Season 6, in which it is made completely clear that SOMEONE died, but viewers had to worry who it was for the entire summer.

All of this is important to understand the death of Lee Everett in the first Walking Dead video game by Telltale Games. Lee is the player that characters control, and he survives a number of improbable zombie adventures along the way. Ultimately, the player can choose to have the little girl Lee protects throughout the game, Clementine, shoot him to prevent him turning into a zombie or to let himself change. Either way, he dies. It's tragic for players rooting for his survival, but it serves as a perfect reflection of the show. Just as characters can be taken away after years of viewers getting to know them, players can lose Lee Everett to a zombie bite after keeping him alive through five episodic games. Later installments feature Clementine and others as protagonists, and Lee lives on in memory. If Lee had somehow survived his zombie bite or been cured or even resurrected, it might have fit in the world of video games—but it would have been completely out of place in the world of The Walking Dead.

Ethan Forrester

Ethan Forrester is a young man that players control in Telltale's Game of Thrones adaptation. Like Lee Everett in their Walking Dead game, he's someone that players get to know quite well before he is brutally killed—by everyone's least-favorite bastard, Ramsay Bolton. It might be tempting to believe he dies simply because that's what happens in the world of Game of Thrones...the aforementioned trope of letting players know that no one is safe. However, his death serves an even more powerful function for gamers: it makes them feel helpless.

That may sound simplistic, but it's actually a very novel sensation in a video game. Games are designed to give the player power and control. If a character is kidnapped, he breaks free from his captors. If loved ones are taken, he travels strange lands and saves them. In fact, this level of control is the entire formula for the Telltale Games series, in which each title is filled with choices about dialogue and action that influence later chapters. However, Ethan's death is a fixed event, as no magical choice of actions or dialogue choices can save his life. Ultimately, this recreates Game of Thrones in a brutally honest way for players, as the show takes place in a world where no combination of wealth, skill, or connections can keep people from being killed in the blink of an eye. And just as the survivors have to witness characters like young Rickon being cut down by arrows, players must watch Ethan bleed out and die, feeling both helpless and enraged.

The Boss

The Metal Gear series of games have always employed a glorious paradox. On one hand, they're fearlessly silly, with characters walking around like Wile E. Coyote in a cardboard box and fighting characters like vampires and evil clones who are also former presidents. On the other hand, each game seems to have a deep and serious perspective on war and death, as with the first Metal Gear Solid's sobering reminder that the threat of nuclear war never truly goes away. Arguably, this motif of life and death reaches its climax at the end of Metal Gear Solid 3, in which the player must kill the character known as the Boss. She is presented as an American veteran of everything from Normandy to experimental spaceflight, but she eventually develops her own agenda, and Snake, the player's character, must fight her to the death.

The climactic fight to the death is standard video game content, of course. What's notable in this game is how she dies. Specifically, the game can't end until the player pushes the button to shoot her. It isn't a cutscene, and the player can wait indefinitely before pulling the trigger. Why did Konami create a game with such a personal ending? Ultimately, the ending sears into the player's brain some of the messages of Metal Gear Solid as a series. For instance, the games often force players to see villains as three-dimensional characters with their own fears and motivations.

Ever since Metal Gear Solid 2, there have been options to non-lethally fight most of your opponents. All of this means the player understands that taking someone's life is a powerful choice, one that has deep philosophical ramifications. In the case of the Boss, players now understand her entire sympathetic story as a patriot who had been betrayed and abandoned by her country. Even in the final moments of the game, it comes down to a fateful choice. Players can walk away from the controller, turn the system off, and move away from the game, knowing they left their mission unfinished—or they can complete their duties as a virtual soldier via coldhearted murder. In the final irony, the player's character from Metal Gear Solid 3, a prequel game, becomes the main antagonist of the original Metal Gear games, and the end of this adventure allows players to feel firsthand the horror and cruelty that shapes him into a future supervillain.

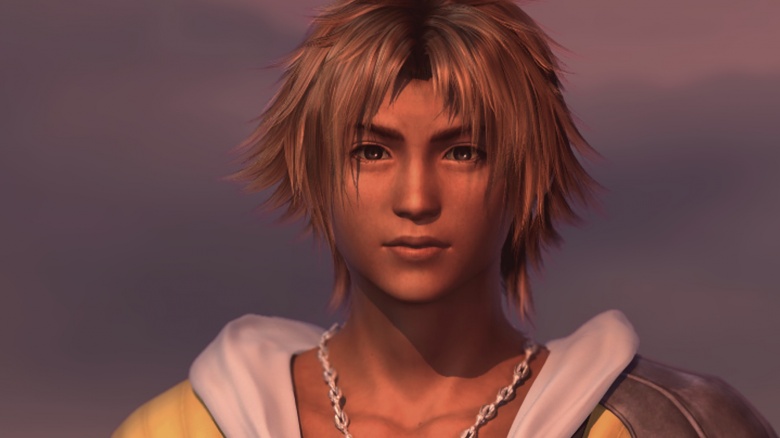

Tidus

Tidus is the divisive main character of Final Fantasy X. His story starts out as, seemingly, one of time travel. His home is attacked by a creature named Sin, and when he wakes up in a strange land, everyone refers to his home as a place that was destroyed over 1,000 years ago. Over the course of the game, he realizes this is only partially true. It turns out that Tidus and his home are living dreams from creatures called the Fayth who are magically recreating a real place and people who were wiped out. It was only via Sin's attack that Tidus crossed over into the real world. The Fayth can use their power to destroy the world-threatening Sin permanently, but there's a pretty big catch: they will no longer be able to dream, meaning that Tidus will die after Sin does. Tidus does the noble thing and agrees, and their word is true: after Sin is defeated, Tidus fades into nothingness, leaving many players to wonder exactly why.

The answer is that Tidus dies so players can understand love. Most of the time, video games in general (and Final Fantasy games in particular) are guilty of portraying love as a simple matter of physical romantic attraction. Tidus goes much further, literally giving his own life so that his love, Yuna, can live completely. On a larger scale, the sacrifice of Tidus may deliberately invoke Christianity. This game is widely known for its sweeping criticisms of organized religion and many jabs at Western religion, complete with corrupt religious officials and a worldwide belief system that is legitimately proven false. Tidus, though, embodies the best of the Christian ideal of sacrificial love.