The Ending Of Sifu Explained

When Sloclap first teased "Sifu" at the Future Games Show in 2021, no one really knew what to expect. The game seemed to follow a singular protagonist – either a man or woman, as chosen by the player – down a dark path of revenge. As the protagonist battles innumerable baddies, they visibly age, growing gray hair, their skin wrinkling before players' eyes. While the aging mechanics didn't fully make sense at first, they looked beautiful and left players wanting more.

Now that "Sifu" has arrived on PlayStation 5 and PC, gamers have all the answers about the martial arts brawler. Critics have already pointed out that the game is incredibly difficult, and that its complicated relationship to Chinese culture is worth discussion. That being said, players can allegedly beat "Sifu" in about 10 hours, making it worth a spin. Despite its short story length, truly beating "Sifu" requires dedication both to the game's difficulty and its measured philosophy – which might draw the game out to many, many more hours of playtime.

For those who want to work through the entirety of "Sifu," here's what the ending holds, as well as what lessons players can draw from it.

Beware of major story spoilers ahead for "Sifu."

A Path of Revenge

For the most part, "Sifu" is a story about revenge. Many, many kung fu films have focused on revenge, and "Sifu" is a love letter to the genre in almost every way, as created by its decidedly Western developer, Sloclap. Though Sloclap did hire consultants to work on its implementation of Pak Wei kung fu styles, it noticeably did not work with any actual Chinese practitioners on "Sifu" – a fact that has drawn ire from some corners of the gaming community (per GameByte). While the morality of racial politics in "Sifu," as well as its representation of China as a whole, could be debated, its kung fu heritage is something that speaks to all sorts of audiences, just like the many great films that have come before it.

Grady Hendrix and Chris Poggiali's survey of kung fu history in America, "These Fists Break Bricks," argues that kung fu movies have always had a chokehold on a wide variety of audiences because they deal with simple, relatable themes that never go out of style. For example, Latinx and Black audiences made up a large percentage of kung fu film fans in the 1970s because these films' protagonists dealt with issues relevant to the real world, like experiencing Otherness, standing up to authority, and seeking justice for wrongdoing. "Sifu," like martial arts films of the past, features a protagonist that must stand up to power in order to avenge their murdered father.

What happens to Yang's gang?

Yang, along with his four gang members – Fajar the Botanist, Sean the Fighter, Kuroki the Artist, and Jinfeng the CEO – are responsible for breaking into the protagonist's home and murdering their father, all while they look on helplessly from a cupboard. "Sifu" doesn't provide an explanation up front for why Yang killed the elderly man, and it makes players work for answers. Throughout the first half of the game, the protagonist must journey through the gang's different lairs, with each level culminating in a punishing boss battle.

For what it's worth, the gang doesn't seem to be working together anymore, though astute players can find connections between certain members. All of them seem to have varying degrees of wealth and power, which is reflected in their respective levels. Fajar, the first boss of "Sifu," lives in "The Squats," a run-down drug den, whiled Kuroki seems to reside in a beautiful contemporary art museum, complete with a full staff of bodyguards. Regardless of how each member of Yang's group ended up in their locations, it's clear that they're all responsible for this horrible crime, and therefore must be taken out appropriately. And so that's what happens, eventually leading the protagonist to Yang himself. Unfortunately, Yang has more than a few tricks up his sleeves, and the game's not even close to over just yet.

'The End' isn't the end

What seems like the ending of "Sifu" isn't really the ending at all. As the protagonist fights Yang, players can see the ending in sight, but defeating the gang's leader doesn't seem to bring the satisfaction to the protagonist that it should. Just before the fight, Yang calls the protagonist "Little Brother" (or "Little Sister," depending on the player character's gender), signifying the closeness the pair once shared. Yang doesn't seem to want to fight so much as fighting is an inevitability, something that the protagonist has been fighting against for throughout the entire narrative.

When Yang correctly calls out that the protagonist only survived so long because of their seemingly magical pendant of revival, he asks if the protagonist actually fears death. It turns out, they do – for now. The protagonist defeats Yang, but they don't feel happy about it. While their face is at first determined, they then collapse into a state of near tears, mourning the loss of their one-time friend as they realize that justice doesn't always bring spiritual peace. Then, the second half of "Sifu" begins.

Wude and the true ending

In a dreamlike sequence, the protagonist recovers a memory of their father confronting Yang over the pendant. Then, a voiceover explains wude, which the protagonist's father explains is the practice of letting an opponent know that you could defeat them handily, but allowing them to live as a mercy. Wude brings balance to the world, and helps kung fu masters practice their craft responsibly.

Dr. Yang Jwing-Ming from Yang's Martial Arts Association has discussed at length the concept of martial morality, which is what wude is hinting at in "Sifu." Though it has a rich history and philosophy behind it, martial morality consists of a code of ethics that students must adhere to, all of which work together to make sure that they practice martial arts in a level, measured way. Morality of deed forces students to be humble about their abilities, respect others, and seek to do good in the world. Morality of mind, on the other hand, focuses on students' courage and will, getting the mind to line up with physical capabilities in the wisest way possible.

"Sifu" doesn't go too deeply into the philosophy behind martial morality, but it does illustrate that "winning" isn't always satisfying, especially if it means hurting others. The mind and body must align, and so the protagonist must set out to right their wrongs. And so, after thinking the story is over, players suddenly find themselves back at the beginning of the game, once again 20 years old and ready to find Yang's crew.

Where does everyone end up in the true ending?

To really complete "Sifu" and earn a happy ending (well, happier), players must once again fight each boss. This time, the protagonist must break the boss' Structure (or stamina) instead of outright killing them. On this run-through of the game, players have an option they didn't before, and can choose to spare enemies instead of using a takedown move. That being said, practicing wude isn't easy, and defeating bosses in a way that also spare them (by breaking their Structure while not doing too much damage) is a difficult task.

As players spare each boss, they see a different conclusion to the battles they've already fought. In addition to the new reactions from bosses, a Chinese character appears on a wheel, indicating that the protagonist is one step further down the path towards understanding wude and achieving mercy for their enemies.

In the true ending of "Sifu," players don't exactly know where the bosses end up, but they definitely make it through alive, potentially to understand new aspects of themselves and realize their own place within a more ethical system of martial arts.

All bosses have secrets in the end

As players revisit levels, they'll likely find information about and connections between each boss that shine new light on their pasts. Before "Sifu" was released, Sloclap Executive Producer Pierre Tarno told MP1st that " there are a couple of hidden secrets inside the game that might take a couple runs for players to fully understand." Those secrets come in the form of small pieces of information that players can find littered around the each level. It's not easy to come by this info by any means. A key in the fourth level might unlock a door in the first level, for example, forcing players to wait for a new loop in order to properly piece together the game's story. That being said, finding out each boss' backstory is set up as a core component of "Sifu."

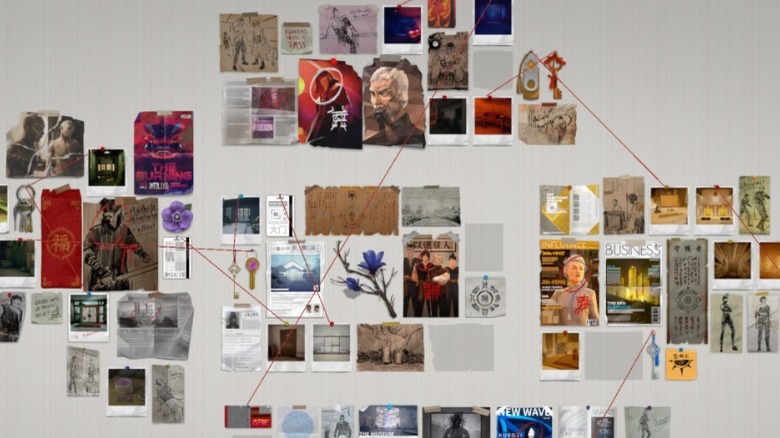

At the beginning of the game, players consult a detective board, which the protagonist has erected in their home in order to keep track of Yang's group. The board has a section for each boss and blank spots where information will eventually appear once found. As they accumulate items from each level, the protagonist finds out each boss' dark secrets, like the Botanist's terminal illness, the Artist's dead twin sister, and the Fighter's deceased father. These details help flesh out the world of "Sifu" and provide reasoning for the way each boss behaves, making them worthy of the mercy the protagonist deals out in the second half of the game.

Sifu's use of time changes the story

"Sifu" plays with time, and depending on what age the player is at each leg of their journey, players could read the game in a variety of different ways. Beating all bosses at age 20, without dying once, feels like a different story than beating them at 70, after years of hatred and practice. Additionally, "Sifu" plays with time by essentially restarting the game with new options after the player kills Yang, who should be the final boss. Players start back at the Squats at age 20, ready to choose a new path for themselves, all the bosses they killed now alive again and capable of being spared.

Yang alludes to the pendant being magic, and seems to possess some magic of his own. Before fighting him, the protagonist sees Yang kill a bird and bring it back to life, the bird flittering to safety. He asks the protagonist if they'd be willing to bend the rules in order to save those they love, and readers might guess that Yang once did as he suggested, using the pendant's power to manipulate life and death to protect someone he cared for. While "Sifu" doesn't go into detail about Yang's past, the pieces are all there, setting up a tale of revenge, then mercy. The protagonist – and players – realize that wude is the more balanced approach, and time reverses to accommodate that change of heart. That being said, time isn't subject to the protagonist's whims, and everyone dies eventually.

What happens to the protagonist?

In a weird twist of fate, the protagonist must die at the end of "Sifu" to truly practice wude. After sparing each boss in a second runthrough of the game, players arrive once again to face off in a brutal fight against Yang. True to their father's teachings, the protagonist can spare Yang, triggering a third and final phase of the battle. They hear their father say, "This is wude," before collapsing into a heap on the ground, potentially succumbing to their own injuries. They wake up on an idyllic mountainside, taking in the misty peaks and smiling before taking in one final, poignant breath. Then, the credits roll and players are left to interpret the ending as they choose.

It's unclear if the protagonist dies, though the "good" ending seems to suggest so. In an after-credits scene, players see someone a young person calls "sifu" putting down the pendant before walking out of the room. The short scene doesn't show this sifu's face, leaving players to interpret if the protagonist lived after all or if Yang perhaps picked up the pendant and started on a new path. Either way, "Sifu" forces players to wrestle with themes of revenge and forgiveness without downright telling them how to feel about the events of the game, and maybe that's the best teaching of all.