Video Games That Were Banned In America

In the United States, freedom of expression is guaranteed under the First Amendment of the Constitution. While this means that video game companies can release pretty much any game they want, it doesn't mean they won't face consequences in the marketplace when they release a product that's overtly violent, controversial, or overall tasteless. Individuals, cities, and the court system have stepped in a few times to try to recall, cancel, or destroy video games considered unsuitable for audiences—and here's a look at the long, lurid history of some of the most memorable examples.

The Guy Game

Young heterosexual dudes will always be desperate to see women remove their clothes, although the delivery method has taken on different forms over the years. In the early 2000s, guys got their nudity fix with Girls Gone Wild, the bestselling line of softcore pornography consisting largely of footage of college-age women partying and stripping during spring break. GGW copycats hit the market, too, including the 2004 interactive title The Guy Game.

Released by a classily named publisher called Top Heavy Studios, the console and PC game required players to guess how scantily clad women would answer a trivia question. If the player predicted correctly, their reward was a clip of a real San Padre Island reveler disrobing. After the game hit stores, one of the topless women featured in The Guy Game sued—because she was only 17 when she stripped for the camera. Seeing as how The Guy Game was now child pornography, the Travis County, Texas, judge who heard the suit ordered all copies to be removed from stores.

Thrill Kill

In August 1998, gaming juggernaut Electronic Arts purchased large swaths of Virgin Interactive, acquiring not just an extensive back catalog of games, but also the rights to yet-to-be-released titles, such as the PlayStation title Thrill Kill. An extraordinarily violent and gory fighting game in the vein of Mortal Kombat or Street Fighter, Thrill Kill was even more violent and gory. It pitted contestants sent to Hell against one another, fighting for the right to return to Earth by employing strategies like ripping off an opponent's arm and beating them with it, or shoving a cattle prod into their adversary's throat. For such content, Thrill Kill earned an AO, or "Adults Only" rating from the ESRB. That only confirmed EA's decision to pull the game from the release schedule. "We have to be responsible for the content that we make available to the marketplace," said Pat Becker, EA director of corporate communications." "We felt that this was not the kind of title that we wanted to see in the market."

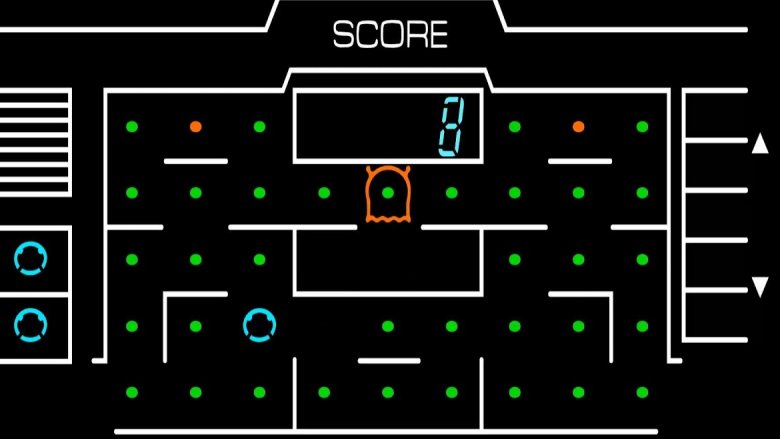

Various Pac-Man clones

In the early 1980s, Pac-Man was a cultural phenomenon—and a cash cow. Unsurprisingly, other companies released their own circle-eats-dots-in-a-maze games, and Pac-Man rights holders Atari and Midway fiercely defended their property in court, seeking and receiving injunctions to end the sale of clones. Among the games pulled were the arcade title Mighty Mouth and a handheld game called Packri-Monster. Not only was that game's name a likely cribbing, but so was the premise: The game's packaging depicted a round blob, a ghost-like creature, and the tagline "Gobble or be gobbled!" Midway also stopped a company called Arctic, which sold printed circuit boards with which computer enthusiasts could build their own video game called Puckman. It was such a thorough copy of Pac-Man that it took the game's original title and included a glitch from the Pac-Man code.

Custer's Revenge

Despite pixelated, typical-for-1982 graphics, Custer's Revenge didn't leave much to the imagination. The player controlled real-life 19th century military leader General George Custer...who is naked, sports an erection, and tries to rape Native American women.

Needless to say, the game was highly controversial. It was built for play on consoles made by Atari, which sued Custer's Revenge manufacturer Mystique to keep the game from hitting stores. In some places, such as Oklahoma City, it was available only at adult bookstores. Oklahoma City's city council also passed a resolution that called Custer's Revenge "distasteful" and "not in the best interests of the community." Other groups protesting the game included the Urban League, the Young Women's Christian Association, and multiple Native American associations. While no government ever technically banned the game, Custer's Revenge's manufacturer responded to the negative attention by voluntarily ending production on the title.

Baby Shaker

By and large, smartphone games are simple, straightforward, and easy to play. The objective of Angry Birds is easy to understand (fling birds at stuff), as is Sikalosoft's Baby Shaker. A picture of a baby appears on the screen, and it cries and shrieks. The player shakes their phone until the baby stops crying and two red Xs appear over its eyes—because it's dead. Soon after Baby Shaker hit Apple's App Store in 2009, the protests began. For example, Patrick Donohue of the Sarah Jane Foundation, a pediatric brain injury awareness group, wrote a letter to Apple decrying how the game made a joke out of child abuse and/or infanticide. Apple quickly pulled the game.

Too Human and X-Men: Destiny

Countless games featuring Marvel's crusading mutants have been released over the years, so what was it about X-Men: Destiny (and the science-fiction/mythological action game Too Human) that got it yanked out of stores? Copyright issues. In 2004, Epic Games debuted Unreal Engine 3, a revolutionary set of software development tools that made games more detailed and lifelike than ever. Epic was very careful about which studios got to use the engine and how—and a company called Silicon Knights became so frustrated working with Epic (and Unreal Engine 3) that it sued for breach of contract. Further, the suit claimed Epic had willfully sabotaged "efforts by Silicon Knights and others to develop their own video games." Silicon Knights ultimately lost the suit, and a district judge found that the developer had "repeatedly and deliberately copied significant portions of Epic Games's code containing trade secrets." Silicon Knights was ordered to pay Epic $9 million, as well as recall and destroy any and all unsold copies of X-Men Destiny and Too Human.

Death Race

Compared to today's video games—especially the violent ones—the 1976 arcade game Death Race seems innocuous and quaint. Small white "gremlins" run around a black background, while with a steering wheel mounted on the cabinet, players controlled a car. When the player ran over a gremlin, the game would let out an eerie scream, and the gremlin was replaced with a tombstone. In other words, it was a driving game where the objective was to nail pedestrians. (Game creator Exidy reportedly developed Death Race with the working title Pedestrian.)

When Death Race cabinets started to show up in arcades, bars, restaurants, and amusement parks, it became the center of one of the very first video game controversies. A local politician in Spokane, Washington, quoted Dr. Gerald Driessen of the National Safety Council, who called the game "gross." After receiving complaints, an amusement park in Illinois removed the game from an arcade, while a distributor in Chicago stopped offering the game and owners of arcades and other businesses simply refused to buy or rent a Death Race cabinet. Of course, in some places, it had the opposite effect—Exidy moved more than 1,000 machines, at least doubling its sales figures.

The AO rating

In the U.S., determining the proper audience for most works of entertainment is fairly cut and dried. The Motion Picture Association of America rates movies anywhere from "G" to "NC-17" to help parents determine if they're appropriate for their kids. TV shows bear a similar rating, such as "Y" (for "youth") or "MA" (for "mature audiences"). The video game industry's rating system is more complicated.

The Entertainment Software Rating Board (or ESRB) calls itself a "self-regulatory body that assigns ratings for video games and apps so parents can make informed choices." That means the game industry polices itself. The ESRB doesn't outright ban anything, nor does it have the authority to do so—the most it can do with an ultra-violent or sexually explicit game is slap it with an "AO" or "Adults Only" rating.

Even that doesn't really do much to halt sales to minors. In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that video games are a form of constitutionally protected art, and to restrict their sale based on violent content is illegal. Nevertheless, the ESRB operates the ESRB Retail Council, whose member retail stores promise to not sell AO-rated games to kids. Some stores, such as GameStop, go even further and don't mess with selling controversy-riling AO tiles whatsoever.

All arcade games (in Marshfield, Massachusetts)

The early years of video gaming produced a lot of controversies—so much so that one town decided it didn't want any games at all. In 1982, the residents of Marshfield, Massachusetts decided that arcade games qualified as "coin-operated amusement devices," which the town had banned a decade earlier. Result: A ban on all public video game cabinets. When local businesses that wanted to offer video games challenged the ruling, the Supreme Court upheld the ban. Two more town-wide votes over the years affirmed the ruling. Finally, in 2014, the law was rescinded, and arcade games—long since rendered virtually obsolete by sophisticated home gaming consoles—finally popped up in Marshfield restaurants and bars.