The Untold Truth Of The Creator Of The NES And SNES

The Family Computer (or Famicom), known as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in the Americas and Europe, changed the world in 1983. The 8-bit home console broke new ground for graphics and set expectations for the next 40 years of console gaming. Known for launching legendary franchises like "The Legend of Zelda" and "Metroid," the NES was ground zero for everything that came after it in the gaming world.

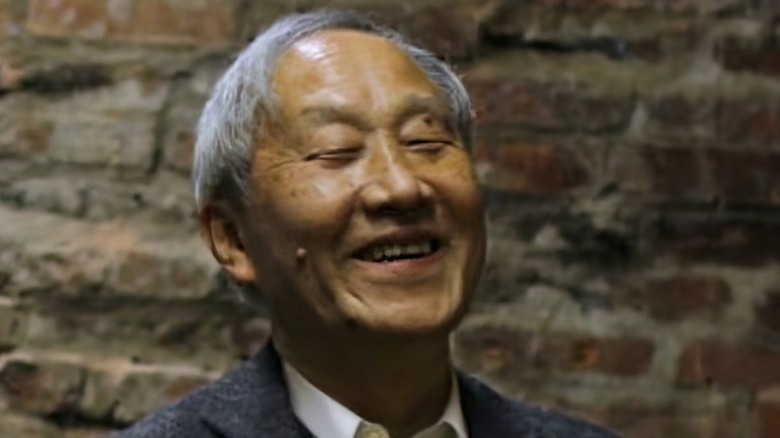

On Dec. 6, 2021, Masayuki Uemura, father of the NES, died at age 78. The Japanese engineer and designer was one of the most influential creatives in all of gaming and worked for Nintendo from the early 1970s until after the mid-2000s.

Uemura was the lead architect on the NES, as well as its successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES). In the decades since, his innovations have been built upon by the dozens of classic video games and platforms released by Nintendo. But without Uemura's contributions, the landscape of console gaming would look completely different today.

Masayuki Uemura's father was a kimono merchant before getting into tech

Masayuki Uemura was born in Tokyo in 1943. According to a profile by the New York Times, Uemura's father was a kimono merchant in the city, but Uemura and his family had to relocate to Kyoto when he was very young, due to the bombing raids that became commonplace during World War 2. This re-location led Uemura to spending his youth growing up in the countryside of Kyoto. His father would go on to own a record store, which may be how young Uemura began to develop an interest in electronics and engineering.

Growing up, the young creator would dabble in making radios and even built his own pachinko machine. After school, he went on to the university level to study electrical engineering at Chiba Institute of Technology. Uemura wanted to make color TVs, but the work he did in the world of televisions outdid even his grandest dreams at the time.

He worked on the predecessor to Duck Hunt

In the early 1970s, Uemura was gainfully employed in the tech world, working at electronics manufacturing company Sharp. In 1971, he began talking with Gunpei Yokoi, Nintendo's head toy designer, about using Sharp's photo cell technology to create a new light-gun peripheral for the burgeoning video game company (per Eurogamer). It was that same year that Uemura was hired on to the team at Nintendo, with the goal being to turn this idea into a reality.

The work Uemura first started when he began eventually became The Laser Clay Shooting System. This would end up being the predecessor to "Duck Hunt". Released in 1973, the light gun system used an overhead projector to display its (at the time) cutting-edge shooting gallery. Subsequently, both he Laser Clay Shooting System and the more successful (and cheaper) "Mini Laser Clay" could be found in arcades and bowling alleys in Japanese cities in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Uemura's "Breakout" system

The Famicom and NES were far from Nintendo's first foray into video game hardware. For instance, Nintendo broke into the handheld market with the release of the first Game & Watch in 1980. And while it is easy to retrospectively draw a straight line between the success of the Game & Watch and the creation/design of the NES, Uemura didn't actually work on these handheld devices. Instead, it can be argued that the project that set him up for success most was working on the Color TV-Game Block Kuzushi, a version of Nintendo's first home console line, the Color TV-Game. That's right, before the NES, the toy company was already transitioning to making games for home televisions.

This game, otherwise known as "Breakout" if directly translated to English, was a block-breaking game like Atari's game of the same name. The home console, which featured built-in games, was a big learning opportunity for Uemura as a creator.

"This was the step I started to learn the technology behind connecting a game system to a TV and having your images display on a TV," Uemura said to USGamer. "This allowed us to grab hold for the first time the idea of using the television for something other than watching TV. That wasn't really a concept people had in Japan at the time."

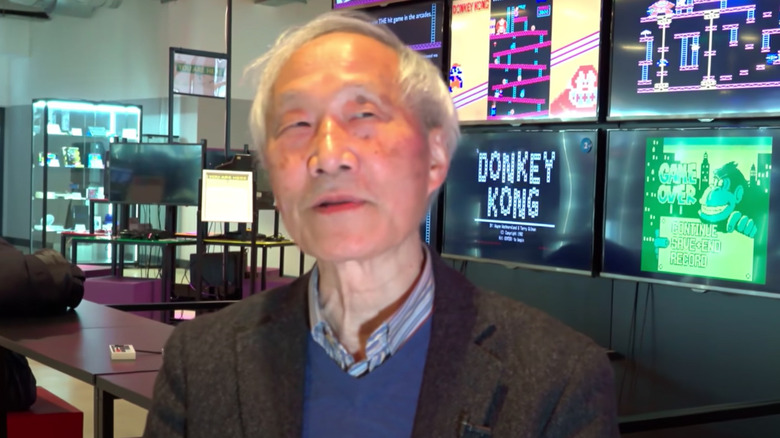

The Famicom was initially built as a machine to run Donkey Kong at home

While it eventually became most well known for games like "Super Mario Bros.," the Famicom was originally designed as a proof of concept for bringing Nintendo's biggest arcade hit home. That's right; the Famicom was first built as a way to bring "Donkey Kong" from the arcade into the homes of the paying Japanese public.

As Uemura explained in an Iwata Asks interview, the challenge for his team was to and his team was to make "Donkey Kong" run on a small one-chip circuit board. Working with the engineers at Ricoh, Uemura's team worked day and night to achieve one goal: bringing "Donkey Kong" home. The successful result was the beginning of the most formative home console ever created.

Ironically, while versions of "Donkey Kong" and "Donkey Kong Jr." would eventually launch with the Famicom in July 1983, these games wouldn't make their way onto the NES in America and Europe until 1986. This was well after the launch year's release of "Super Mario Bros." and the original NES sports game library.

Why Uemura's team used the NES D-pad

In the 1980s, joystick models were popular in arcade machines and other home consoles. The most prominent example of this trend may be the Atari 2600, which was released in 1977, less than a decade before the NES set the course for Nintendo's 2D output. So why did the NES go a different way? There was one major reason why Uemura and his team made this choice, and shockingly, it wasn't the cost.

According to Uemura (in an interview with Nintendo Dream Web), the choice to use a "cross pad" — or directional pad, as its more commonly known in the US — was inspired by an ease of use and safety concern. According to the designer, the team did not want children to step on it and injure themselves or break the machine. There was most definitely a legal element to this business decision as well. Nintendo naturally wouldn't have wanted angry parents to bring up lawsuits. Thankfully, Uemura's design choice was a smart creative decision that avoided the heat entirely. In fact, throughout the development process of the NES, Uemura's responses to Nintendo's demands led to some iconic design choices.

Design changes, repairs, and discovering Super Mario Bros.

There used to be a larger gap in time between releases of Japanese consoles overseas and in the United States. Home systems like the SNES and NES were renamed and re-designed for release in America, which led to a delay. Aside from the name change, one huge difference between the Famicom and NES was the size of the cartridges. In fact, NES cartridges were nearly twice the size of the Famicom's.

The reason for that difference, as it turns out, is humidity. In an interview with Nintendo Life, Uemura explained that the smaller cartridges were a result of another redesign decision. The Famicom was a top-loading console, which meant cartridges were smaller. Japan has high humidity, but in drier areas — like many regions in the US — top loaders create a good deal of static. Thus, the NES needed to be a front-loading console, which in turn led to the larger cartridges.

Speaking of cartridge-based games, Uemura didn't know that "Super Mario Bros." was being developed — that's how knee deep he was in repairs following a slow launch of the Famicom. There was a lot of trial and error involved in designing and maintaining the original Famicom, even after launch. Instead, Uemura discovered the legendary "Mario" game was coming out through a commercial on TV.

Uemura retired from Nintendo in 2004, but never gave up games

After he worked on both the NES and the SNES, Masayuki Uemura remained at Nintendo for 15 more years. He went on to be a producer and advisor on many Nintendo releases of the '90s, including "NES Open" and "Super Mario Bros. Deluxe" for the Game Boy Color. His final project at Nintendo was as a Manager on "The Legend of Zelda: Navi Trackers," a side mode for "Four Swords Adventures" that never saw release in the US.

In 2004, Uemura retired from making games and went on to become the director of Game Studies at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto. He continued to teach students about video games until the final year of his life, leaving the role in March 2021. The University announced his passing on Dec. 9, 2021.

Umeura was quite literally a lifelong creator; his work in hardware development, and teaching, is a reminder that video games can be a source of connection with others.